On 1st February 2023, the Ministry of Finance announced the Union Budget for the financial year 2023-24. The next day various newspapers and web portals commented upon the Union Budget 2023-24, and many groups organized discussions and post-budget consultations. Among those groups, a majority deliberated on the share of the social sector in the Union Budget. One important sector among these, which remains a topic of discussion is Education. The budget increase compared to the Budget Estimates (BE) of 2022-23 and Revised Estimates (RE) of 2022-23 has been lauded as a budgetary increment by newspapers and web portals in the allocation for the Ministry of Education.

This article will attempt to analyze the quality of the allocation for the education sector. The education budget can be assessed by looking at the share of the budget in terms of GDP, percentage share of the education budget in total expenditure budget and its trend in the last five years, key highlights of various departments of the Ministry of education and key highlights of various flagship programs and schemes. One important step to looking at the budget is to assess the current volume of the education system (enrollment rates, number of education institutions, status of teachers, etc.) and the current needs of the education system.

The Budget 2023-24 reignited a discussion about the educational spending percentage of GDP. This is inevitable because looking at educational spending from an angle of the percentage of GDP suggests that the citizens try to reflect on how far the current spending on education helps the development of an economy.

Educational spending and the genealogy of 6% of GDP in education

In the last two decades, India’s education sector has witnessed massive expansion in terms of schools, colleges, universities, and enrollment. This expansion generated two problems: lack of equity and quality. To address these challenges, a country’s education system needs to spend appropriate money. A budget for the education sector can be the first step in this regard. Because BE does not mean an actual amount for education, rather, it is just an estimated allocation that is not necessarily going to be spent in the financial year. So, healthy and appropriate allocation can express the intent of the government towards the education sector. Covering a vast education system from school to university requires an appropriate amount of allocation of financial resources to address the challenges and problems that exist.

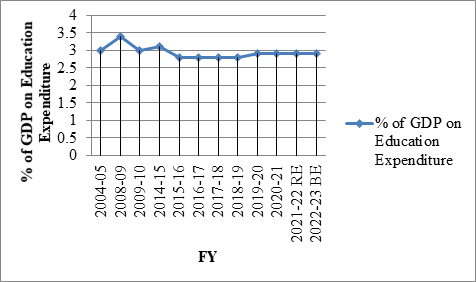

Major developed and developing economies have realized the importance of education in human development as well as the need to impart quality. Hence, these countries allocate substantial amounts to the education sector. In India, the Education Commission 1964-66 which is popularly known as the Kothari Commission also realized the need of allocating an appropriate amount for the education sector. The commission recommended that “if education is to develop adequately, the proportion of Gross National Product (GNP) allocated to education will rise … to 6.0 percent in 1985-86”. Later this recommendation was accepted by National Policy on Education in 1968. As J.B Tilak argues, this recommendation of the Kothari Commission was misinterpreted and political parties created controversies around the recommendation and argued that it was redundant because the country is spending more than 6% of GNP if the spending of the central government, state government, and private spending by the families is considered. But this controversy was settled by the common minimum program of the UPA government (7th June 2004) by pledging to spend 6% of GDP on education. The document said, “India’s greatest resource is its people. The full potential of our human resources has yet to be effectively utilized. High priority will, therefore, be accorded to education. The Government will aim to increase public education spending to reach at least 6% of GDP, with half the amount earmarked for primary and secondary education.” Though UPA-1, 2004 ambitiously pledged to spend 6% of public spending on education, even 3.5% of GDP was not crossed even if one combined the spending of both the state governments and the central government. During 2004-05, the public expenditure on education was 3% of GDP and increased it to 3.4% of GDP during 2008-09. During 2009-10 education expenditure further came down to 3% of GDP. During the early period of NDA, the education expenditure was at 3.1% in 2014-15 which again declined to 2.8% in 2015-16. Since then it has been constant between 2.8-2.9 percent from 2016-17 to 2022-23. The marginal growth in this percentage occurred only during the year National Education Policy was introduced. The almost flat curve in the below graph for the last ten Financial Years (FY) suggests that despite massive growth in the volume of the education system the education expenditure is only half of what DS Kothari recommended more than fifty years ago.

Source: Author’s calculation from various documents referred to in the article

In the last decade, an interesting development happened in the arena of education in the form of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020. NEP 2020 came into the picture after 28 years of National Policy on Education 1992, after 54 years of the Kothari Commission, and after 16 years of UPA-1’s common minimum program which recommended spending at least 6% of GDP in the education sector. The NEP 2020 observes and promises that “The Policy commits to significantly raising educational investment, as there is no better investment towards a society’s future than the high-quality education of our young people. Unfortunately, public expenditure on education in India has not come close to the recommended level of 6% of GDP, as envisaged by the 1968 Policy, reiterated in the Policy of 1986, and which was further reaffirmed in the 1992 review of the Policy.”[7] The policy further says, “The Centre and the States will work together to increase the public investment in the Education sector to reach 6% of GDP at the earliest. This is considered extremely critical for achieving the high-quality and equitable public education system that is truly needed for India’s future economic, social, cultural, intellectual, and technological progress and growth.” (Ibid)

In conclusion, given the importance of public spending in the education sector, the above data suggest that pre-NEP 2020 and post-NEP 2020 the public spending in the education sector as a percentage of GDP is constant and did not budge. On the other hand, the system of education from school to university witnessed massive growth in terms of several educational institutions, enrolment rates, and several teachers. Also, the system still witnessing a huge number of dropout rates at the secondary level of schooling, and various educational targets have been taken in the NEP 2020. How far the current 3% of GDP on educational spending is sufficient to address the challenges and aspirations of the Indian education system? And how can the current spending be able to fulfill the needs of the Indian education system?

ADVERTISEMENT

Related post

September 10, 2023